Evoluzione e ridondanza: un contributo da Pietro Omodeo

Riceviamo dal prof. Pietro Omodeo questa riflessione sulla ridondanza nell’evoluzione, che volentieri pubblichiamo

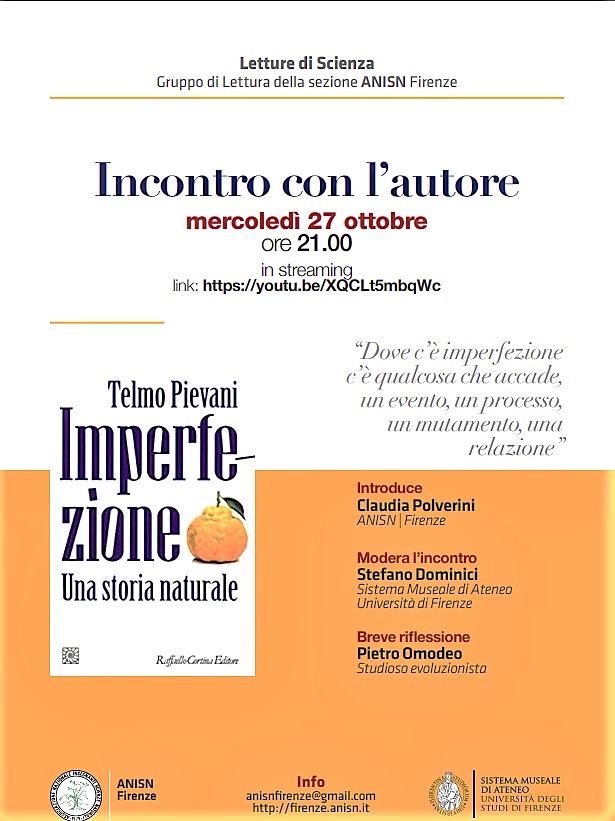

Mercoledì 27 ottobre la sezione ANISN di Firenze, nell’ambito del progetto “Letture di Scienze”, ha invitato ad un incontro in streaming l’autore del libro “Imperfezione”, Telmo Pievani, professore ordinario presso il Dipartimento di Biologia dell’Università degli Studi di Padova. All’incontro hanno partecipato, oltre all’autore, Claudia Polverini (Anisn Firenze) Stefano Dominici (SMA Sistema Museale di Ateneo, Fireneze) in qualità di moderatore e il Prof. Pietro Omodeo.

Nel corso della trasmissione (su youtube è disponibile la registrazione) è stato toccato più volte il tema della ridondanza del genoma degli eucarioti, cioè la presenza di numerose sequenze ripetute (alcune delle quali senza una funzione apparente).

Riceviamo ora dal prof. Pietro Omodeo questo suo articolo/riflessione che volentieri pubblichiamo. Si tratta di un suo contributo inviato alla rivista russa Tsitologya nel 2010, ma poco conosciuto. Di seguito l’abstract e il link per il download.

THE BIGGEST EVOLUTIONARY JUMP: RESTRUCTURING OF THE GENOME

AND SOME CONSEQUENCES

In this paper, the evolution of the cell is investigated till the level of complexity obtained by protists. Particular attention is paid to the genomic compartment and to the question: why has the genome of prokaryotes remained so small over more than 3 billion years and more than 3 trillion generations? Constraints on their genome evolution may be attributed mainly to: 1) the fact that repetitions of nucleotide sequences longer than 12 to 15 bp are forbidden according to Thomas’ principle; 2) the high cost of the control of gene expression by means of regulatory proteins: this cost increases exponentially with chromosome elongation. The formation of chromatin, i. e. the wrapping of DNA around the nucleosomes, removed these constraints and allowed the increase of the genome and especially of the redundant sequences of DNA, whose role is discussed. The transformation and growth of the genome generated a trend towards separation of the various physiological functions and of their control. The formation of a nuclear envelope may have begun with the advent of mitosis, which replaced the simple but delicate device of pushing the newly formed DNA into the daughter prokaryotic cells. An increase of the O2 concentration in waters stimulated further evolution: the new cell established symbiosis with a bacterium capable of protecting against peroxides and performing aerobic respiration. The increased O2 concentration also led to the production of sterols, which became an important component of the cell membrane. The mutual adaptation of cells belonging to different domains involved further modifications, leading to the birth of proto-eukaryotic cells and facilitating the establishment of further symbioses with photosynthetic cyanobacteria. Proto-eukaryotic cells were devoid of motility and contractility, as are the cells of red algae, fungi and Zygnematales today. Both these faculties evolved when the protist eukaryotic cell acquired flagella, cytoplasmic contractility and sensors to govern them.

Nel corso della trasmissione (su youtube è disponibile la registrazione) è stato toccato più volte il tema della ridondanza del genoma degli eucarioti, cioè la presenza di numerose sequenze ripetute (alcune delle quali senza una funzione apparente).

Riceviamo ora dal prof. Pietro Omodeo questo suo articolo/riflessione che volentieri pubblichiamo. Si tratta di un suo contributo inviato alla rivista russa Tsitologya nel 2010, ma poco conosciuto. Di seguito l’abstract e il link per il download.

THE BIGGEST EVOLUTIONARY JUMP: RESTRUCTURING OF THE GENOME

AND SOME CONSEQUENCES

In this paper, the evolution of the cell is investigated till the level of complexity obtained by protists. Particular attention is paid to the genomic compartment and to the question: why has the genome of prokaryotes remained so small over more than 3 billion years and more than 3 trillion generations? Constraints on their genome evolution may be attributed mainly to: 1) the fact that repetitions of nucleotide sequences longer than 12 to 15 bp are forbidden according to Thomas’ principle; 2) the high cost of the control of gene expression by means of regulatory proteins: this cost increases exponentially with chromosome elongation. The formation of chromatin, i. e. the wrapping of DNA around the nucleosomes, removed these constraints and allowed the increase of the genome and especially of the redundant sequences of DNA, whose role is discussed. The transformation and growth of the genome generated a trend towards separation of the various physiological functions and of their control. The formation of a nuclear envelope may have begun with the advent of mitosis, which replaced the simple but delicate device of pushing the newly formed DNA into the daughter prokaryotic cells. An increase of the O2 concentration in waters stimulated further evolution: the new cell established symbiosis with a bacterium capable of protecting against peroxides and performing aerobic respiration. The increased O2 concentration also led to the production of sterols, which became an important component of the cell membrane. The mutual adaptation of cells belonging to different domains involved further modifications, leading to the birth of proto-eukaryotic cells and facilitating the establishment of further symbioses with photosynthetic cyanobacteria. Proto-eukaryotic cells were devoid of motility and contractility, as are the cells of red algae, fungi and Zygnematales today. Both these faculties evolved when the protist eukaryotic cell acquired flagella, cytoplasmic contractility and sensors to govern them.